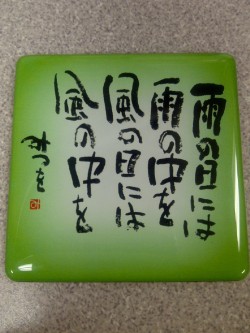

The photo above is a magnet I bought several years ago from the Japan pavilion at Epcot in Walt Disney World. It was a moment of Zen amid an otherwise less-than-tranquil experience in one of the busiest, dizziest (and most humid) tourist destinations on the East Coast. Who knew the House of Mouse could offer such sage wisdom?

“On rainy days, be in the rain. On windy days, be in the wind.”

I understood the maxim’s message right away, as I was still in my honeymoon phase of my yoga and meditation practice and was obsessed with perfecting presence of mind.

What the magnet means is that when you are standing in rain, see it as just rain. No judgement, no attaching “good” or “bad” or “miserable” labels to the meteorological phenomenon. When it rains, be present; see it at its most basic state: water falling from the sky. And then just experience it in all its wet glory.

Same goes for the wind: I feel a strong rush of air pushing at my body and causing my hair to whip around my face. Wind is neither good nor bad; it is wind, and I am standing in it.

The thing is … it’s really hard to master that philosophy, mainly because of something called feeling.

Feeling is something humans are really good at. We have a deep capacity to love and fear and want and reject.

When we’re presented with a simple phenomenon, be it weather or meeting a new person or watching an animal out in nature, the act of observing is usually upstaged by our tendency to want to assign it an emotion or metaphor.

There is nothing wrong with this, but making the leap from observing to feeling can be tricky.

As 5Rhythms® teacher and Open Floor co-founder Lori Saltzman said, “Adding feeling and making meaning is the part that can bring us together … but also the part that gets us into trouble.”

Perspective is powerful.

I and several other dancers got to play around with this concept recently with Lori at her “Write of Passage“ dance/writing workshop, which I attended in Charlottesville, Virginia.

For example, she offered: Imagine a young man in his 20s walking down the street in a hoodie. That’s the baseline, the observation. But one person may see this man as dangerous. Another person thinks, “Oh, what a hottie! I’d like to hook up with him.” And yet another person sees the same man and with a heavy heart thinks, “That’s my son.”

With that, Lori had us put on our “sacred reporter” hats, pull out our notebooks and pens, and observe a volunteer dancer posed in the middle of our circle.”Describe what you see,” Lori instructed, “but only what is right in front of you. I’m talking simple descriptions here—‘white legwarmers, tight ponytail.’ None of this ‘eternal feminine goddess’ stuff.”

We shouted out basic nouns and adjectives, phrases like “bent arms,” “aqua midriff,” “turned-in feet.”

The next step was to describe the volunteer dancer through verbs, action words: “sliding across the floor,” “reaching upward,” “undulating.”

A couple both dressed in purplish hues stepped into the circle. “Now, use metaphors to describe what you see,” Lori instructed. These dancers soon became “two loose grapes rolling around in the fruit bowl” and “grown-up children prancing outside on the playground.”

The final volunteer to step inside the circle was subject to four types of our reporting: basic description, action words, metaphors, and the delicate element of feeling. What type of feeling does this woman’s movement evoke in you? When you watch her move, what is she expressing?

Lori pushed us to be brave, to dare to be wrong in our interpretation. The human race in general can be so afraid to find feeling in another’s expression, because we are afraid of getting it wrong. Of thinking someone is sad when she isn’t really sad.

However, taking the leap and noticing that someone is mourning a loss or experiencing profound happiness—and letting him know that you see what he feels—can be liberating for that person. To be fully seen is a gift!

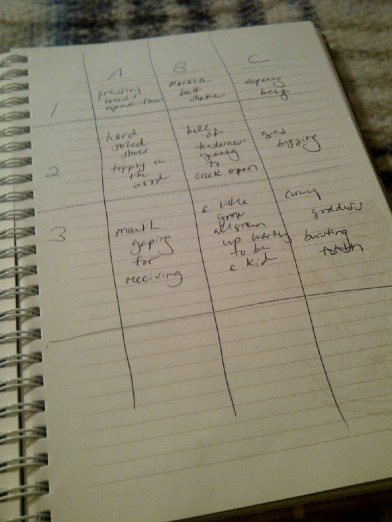

We drew a table with nine cells in our notebooks and as our volunteer danced, we filled each cell with one of those four types of observations. At the end of the exercise, we had a kind of “tic-tac-toetry” in front of us, short poetic verses compiled from a row of squares:

“Hard-soled shoes tapping on the wood / ball of tenderness yearning to crack open / eyes begging.”

Eventually, we all became the moving volunteer, dancing our dance in groups of three as the two other group members took notes in the same fashion, this time on index cards.

When I was done dancing, my fellow group members slid several cards my way, each piece of paper containing a description of how my classmates saw me. There was my dance—me at my most honest—spread out in front of me.

Lori gave us time to sort through the cards, rearrange them a bit, remove a few, and edit slightly. The result was our poem. Here’s mine:

Here I Am.

Rolling it out, shaking it loose.

Letting go.

*Graceful fire*

I am integrated,

A wild child transformed into an aligned woman.

I Am Here.

The day’s lessons and exercises put me in such “sacred reporter” mode that my poetic perspective was in high gear, even off the dance floor.

When I returned to my host’s house that afternoon, I delighted in the fact that the blanket in the guest bedroom had been elegantly twisted and tucked into an abstract figure of the female form, a pear-shaped flow of fabric starting slender at the top and expanding into wider curves at the bottom.

I smiled and snapped a photo, thanking my partner for creating such a lovely work of bed art. He laughed.

“I didn’t do anything,” he said. “All I did was take a nap, and that’s how the blanket ended up.”

Rain can be rain and a blanket can be a blanket. But sometimes the blanket is an abstract goddess, and we shouldn’t be afraid to say it how we see it.

The power of perspective.

3 comments

Comments feed for this article

Tuesday, March 11, 2014 at 5:23 pm

johannafurst

Fabulous Jennifer! xoxo j

Thursday, March 13, 2014 at 4:06 pm

suegreen301

Thank you for your beautiful perspective on Lori Saltzman’s Write of Passage Workshop. I was there too! You and I were partners for an exercise in which we bore witness to each other as we took turns communicating a poem we had memorized — words that had meaning for us. Lori encouraged us to grow deeper and authentic in our emotional experience of the poem by trying different colors of speech — faster, slower, louder or softer. This was kind of a struggle for me — I’m used to dancing strong emotions, not verbalizing them. But the space was safe to contain whatever emerged. In the culmination, Lori asked us to place our hands on our partner’s shoulders and whisper the poem directly into their ear. Whoa! Really?? And to my astonishment, this was one of the most powerful and electric moments in the workshop.

Breathe your words,

Aural witness.

Way beyond dance.

Thursday, March 13, 2014 at 5:36 pm

Jennifer

So glad you dropped by to read, Sue! Of course I remember you and our poetic partnership. Your description of the poem exercise could be its own separate blog post! You put me right back in that moment of when the repetitive reading of the poem–taking time to feel the words roll of my tongue and be received by another–made me realize that the verse I had memorized was no longer the passage that affected me most strongly. I wouldn’t have been able to figure that out with my loyal aural witness!